Four years ago, my friend and I sat at a picnic table at our community college, the evening before the school shut down for the remainder of the pandemic. We were talking about philosophy: what if everything in the universe—the trees, the lawn, the bench—were to fundamental reality what words are to pure thoughts? Neither of us had an answer, but we thought it was a cool idea.

Questions of consciousness and the nature of reality have made frequent appearances since then: two years ago, a conversation with my professor about philosophy and math; a year ago, a conversation with a friend about emergent consciousness; and this year, several conversations, and two book recommendations from someone at a neuroelectronics conference.

I’ve put off writing about this because the task is daunting; this is my longest post to date, but it only scratches the surface of everything I’d hoped to articulate. The determination to write something came some weeks ago, when a friend was talking about reality as a purely physical and random framework, devoid of free will or soul. “That’s so stupid,” I blurted out, but could offer no alternative framework except: “Not space, not time, but a secret third thing.” The goal of this article is to articulate the modern theories of reality, and the “secret third thing.” I welcome comments and emails as I continue to refine my thoughts on this subject.

Physicalism and the Consciousness Debate

One of the most popular interpretations of reality is called “physicalism,” which assumes that everything in the universe, including non-physical phenomena like love and hate, arises from fundamentally physical things. Existence can be reduced to the smallest units of spacetime and their random interactions.

Biologist or tech developer, the universal assumption is that consciousness is an emergent property of a physical system.

This theory gained traction around the time of Charles Darwin, as civilized man faced an identity crisis, and is popular amongst scientists to this day. The conversations surrounding AI consciousness are a good example of this:

Many developers argue that if AI presents the phenomena that we associate with human consciousness, it ought to be considered conscious. This is analogous to the Turing test for machine intelligence, in that it defines the thing it is testing for by a set of measurable outcomes. If you can do x and y, you are effectively conscious, which is equated with being actually conscious. Making such assumptions is a matter of convenience for developers. As the saying goes, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” We don’t need to know everything about consciousness, just enough to recognize it when we see it in a machine.

Biologists would argue that if we still don’t understand how consciousness arises in an organic system, we can hardly expect to identify it in an inorganic one. Whether biologist or tech developer, however, the universal assumption is that consciousness is an emergent property of a physical system.

Donald D. Hoffman: The Case Against Reality

I bring up the consciousness debate because I think it most clearly demonstrates the prevalent theories of reality. This was discussed at length in The Case Against Reality by Donald D. Hoffman, a cognitive psychologist at UC Irvine. This book was the product of decades of research and conversations with leading scientists, including Francis Crick and Joseph Bogen, searching for the biological basis of consciousness.

Francis Crick was a molecular biologist and neuroscientist, most well-known for his role in determining the helical structure of DNA. In later years, he became interested in consciousness and in 1994 published The Astonishing Hypothesis, in which he states:

“ ’You,’ your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.”

Joseph Bogen was one of the neurosurgeons from California who performed the first split-brain operation for epilepsy in the 1960s (called West Coast butchery at the time). This operation severs the connection between the hemispheres to prevent epileptic activity from spreading to the whole brain. It’s a life-saving procedure, but it can also have strange side effects. Each hemisphere has a mind of its own, and with nothing to connect them, the patient will sometimes behave like two different people.

With this context, Dr. Hoffman launches into a truly astonishing hypothesis: that there is no biological basis for consciousness. He posits that our entire perception of the universe, including our understanding of biology, is only an interface to reality, like the desktop of a computer. Rather than telling us what is really happening, our senses provide the depiction of reality that is most useful for informing our actions.

Rather than telling us what is really happening, our senses provide the depiction of reality that is most useful for informing our actions.

Dr. Hoffman is not saying that our perceptions are inaccurate, but that they are completely wrong. He returns to the illustration of the computer desktop: in no way is the document I am writing like the blue icon that represents it on my screen, and yet it is a useful representation of it. In no way are the letters “T-R-E-E” like the tree outside my window, and yet they are a useful representation of it.

These distinctions between the representative and the actual are easily made, because we invented these representations. The “representations” that make up our perceived universe, however, were not made by us, so we cannot distinguish them from reality. Dr. Hoffman, evolutionary biologist that he is, attributes these representations to billions of years of evolution. How we perceive reality is a matter of probability: what is most likely to ensure our survival is never the truth—the mess of electronics behind the computer screen, for example—but a neat and colorful make-believe.

Dr. Hoffman explains two major theories of reality: that the universe, including conscious agents, is fundamentally spacetime (physicalism), or fundamentally consciousness (conscious realism). The former, as we have already discussed, is prevalent in most scientific circles.

Dr. Hoffman advocates the latter theory, stating in his preface:

“Consciousness does not arise from matter. Instead, matter and spacetime arise from consciousness—as a perceptual interface.”

And, again, in the final chapter:

“If we grant that there are conscious experiences, and that there are conscious agents that enjoy and act on experiences, then we can try to construct a scientific theory of consciousness that posits that conscious agents—not objects in spacetime—are fundamental, and that the world consists entirely of conscious agents.”

- Donald D. Hoffman, The Case Against Reality

Julian Jaynes: The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind

Conventional theories of consciousness hinge on physicalism: that is, the assumption that spacetime is the fundamental reality and that consciousness was an emergent phenomenon of the evolving brain of homo sapiens. A mechanism for this emergence was proposed by Princeton psychologist Julian Jaynes in his 1976 book entitled: The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. He proposed that the hemispheres of the primitive human brain operated distinctly—the right hemisphere included planning and initiative, the left hemisphere included execution, and the communication between these two, rather than occurring through a unified internal dialogue, occurred through hallucinations.

“Volition, planning, initiative is organized with no consciousness whatever and then ‘told’ to the individual in his familiar language, sometimes with the visual aura of a familiar friend or authority figure or ‘god,’ or sometimes as a voice alone. The individual obeyed these hallucinated voices because he could not ‘see’ what to do by himself.”

- Julian Jaynes, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind

He attributes the breakdown of the bicameral mind to the advent of writing and narratization, and proposes that consciousness is rooted in language, especially metaphorical language, which enables the creation of an inner “mind-space.” Jaynes’ theory was revolutionary because it suggested that consciousness emerged as recently as 3,000 years ago. He points to the language of the Iliad—dated around 850-750 B.C.—and earlier writings as lacking evidence of self-awareness, with characters relying on voices of gods to perform actions.

Consciousness is only the brain’s method of communication with itself, and it was language that enabled humans to conceptualize the source and recipient of that communication as one and the same. This is what Jaynes refers to as “the analog ‘I’,” or the self that we imagine as we experience conscious thought.

In 2013, someone on a Julian Jaynes Society online forum asked:

“I don't understand the difference between Jaynes's ‘analog I’ and the regular I. Surely people had a regular pronoun ‘I’ during the bicameral period. What is the difference between this and the ‘analog I’?”

The replies included several good explanations of the analog I but none of the “regular I.” And the “regular I” certainly appears in the passages Jaynes selects as evidence of bicamerality, but only in what a person is quoted as saying. The fact that most ancient writings were third-person makes it convenient for Jaynes to state that neither the writer nor the characters quoted were conscious. As it happens, all of the historical evidence Jaynes presents is correlative. My favorite example is his interpretation of a Babylonian carving from around 1750 B.C.:

“The god is seated on a raised mound which in Mesopotamian graphics symbolizes a mountain. An aura of flames flashes up from his shoulders as he speaks (which has made some scholars think it is Shamash, the sun-god)…. One of the magnificent things about this scene is the hypnotic assurance with which both god and steward-king intently stare at each other, impassively majestic, the steward-king’s right hand held up between us, the observers, and the plane of communication. Here is no humility, no begging before a god, as occurs just a few centuries later. Hammurabi has no subjective-self to narratize into such a relationship. There is only obedience.”

- The Origin of Consciousness, Literate Bicameral Theocracies

(On a side note: this carving appears atop an 8-foot stele erected beside a statue of Hammurabi himself. This is remarkably akin to the Biblical account of King Nebuchadnezzar’s golden image, before which citizens were commanded to bow or be thrown into the fiery furnace.)

Jaynes’ arguments are not conclusive, and I can’t help wondering how his theory would change if we gave “the regular I” of the bicameral period the same credence we give it in the third-person narratives of our age. (And the historical evidence he provides gives us no reason not to.)

If a third-person report quotes someone as saying: “I heard the voice of a god and I obeyed it,” what becomes of Jaynes’ theory if we assume that this is quoting a real person, stating in first person what they heard and did? What if there is an “I” that perceives a voice and obeys it, but is not identified with either the perception or the action? Or in the modern context: what if there is an “I” that imagines itself (analog “I”) and acts accordingly, but is not identified with either?

This is why Jaynes’ theory is contingent on physicalism, because physicalism assumes that anything that cannot be described does not exist. Jaynes equates the “I” of language with consciousness, because language is an extension of spacetime and he is assuming that spacetime is fundamental. If, rather, consciousness precedes spacetime, “I” ceases to be conscious precisely when it becomes language.

Physicalism assumes that anything that cannot be described does not exist.

We perceive ourselves the same way we perceive the rest of the world, and we describe those perceptions in words and in mental abstractions. Jaynes suggests that we are only “conscious” when we are describing our perception of self, either through a mental concept or through our inner dialogue, and this is why consciousness is rooted in language. I would argue that consciousness is a continuous awareness of being—not what we are like, but just that we are—and that it has nothing to do with our perception of the external or internal world. When we use language or mental imagery to describe our conscious experience, we are recording our consciousness in a physical form, not creating consciousness from the form. It is a distinctly physicalist trait to confound the recording with the phenomenon that preceded it.

Consciousness is a continuous awareness of being—not what we are like, but just that we are.

Physicalism veils “the thing in itself” with “the thing as it is perceived.” It examines the veil, every stitch and thread, and never thinks to lift it.

The Thing in Itself

“The thing in itself” has a long history in religion, philosophy and even art. (I’ve mentioned this before, but Art by Clive Bell beautifully describes the artist’s perception of physical things as ends in themselves, devoid of utility or contextual meaning.)

To use religious terminology, everything that exists is fundamentally spiritual, secondarily physical. This is what Dr. Hoffman refers to when he talks of consciousness in and of itself, without any spacetime component. And this is what Immanuel Kant refers to as “the thing in itself” rather than the thing perceived:

“We indeed, rightly considering objects of sense as mere appearances, confess thereby that they are based upon a thing in itself, though we know not this thing as it is in itself, but only know its appearances, viz., the way in which our senses are affected by this unknown something.”

- Immanuel Kant, Prolegomena

Long before Kant coined the phrase, “the thing in itself” was presented in Plato’s Theory of Forms, which declares that the fundamental reality is one of ideal Forms, which our perceived reality can only imitate. He illustrates this in his famous “Allegory of the Cave,” where prisoners who have spent their whole lives in a cave see the true forms of the outside world only through shadows on the wall.

Similarly, the Apostle Paul states, “For now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then”—that is, after death—“face to face,” (1 Cor. 13:12).

Kant believed that this underlying reality was unknowable. Dr. Hoffman rejects this belief and urges scientists to consider conscious realism as a legitimate theory that can be mathematically described. In a 2014 research paper, he proposes a mathematical definition of a conscious agent, described schematically in the figure below:

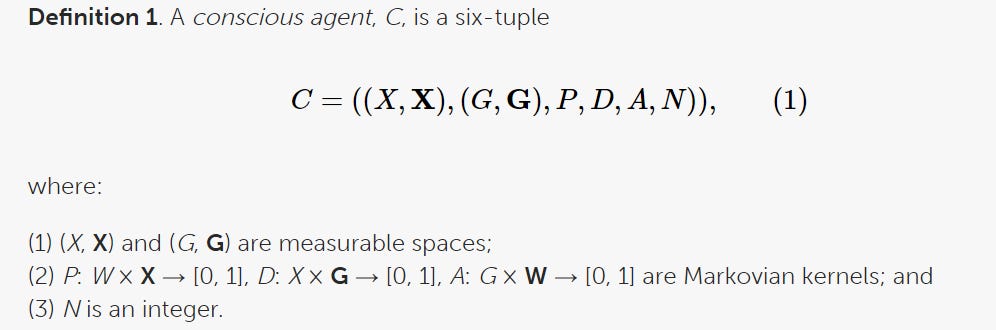

And formally stated in the following definition:

To put it in layman’s terms: he proposes a conscious agent as a fundamental unit of reality, and suggests that these units interact probabilistically to create what we experience as spacetime. He has reduced reality to its most fundamental descriptor—not qualia, but pure mathematics. The universe is no longer atoms, but abstract units of causality.

Mathematics is as close to consciousness as science can ever get, but still it is only a descriptor, not the thing itself.

The most fascinating descriptions of underlying reality come from religion:

Hinduism speaks of a pure consciousness, or Atman, that is the inner essence of every living being. Some schools of Hinduism equate this with Brahman, which is the Ultimate Reality, the essence of everything that exists. This essence takes various forms in the material world, but remains unified, as stated in the Katha Upinashad:

“As the one fire, after it has entered the world, though one, takes different forms according to whatever it burns, so does the internal Ātman of all living beings, though one, takes a form according to whatever He enters and is outside all forms.”

- Katha Upinashad, Hymn 2.2.9

Buddhism teaches a connected consciousness of which we are all components, like beads on a string. The material world manifests and is sustained by the interaction of these components, not as individual entities but as a whole. This is reminiscent of Dr. Hoffman’s description of the universe as a network of conscious agents.

“The belief in an independently existent self is a mistaken perception with serious consequences, for all afflictions are rooted in a fundamental misconception about the nature of the self. Grasping at the mistaken perceptions of oneself and other phenomena leads to constant frustrations, anxieties, and unhappiness. Understanding the illusory nature of the self allows one to experience things 'as they are,' without interference from conceptual constructs.”

- Karma Lekshe Tsomo, Into the Jaws of Yama, Lord of Death: Buddhism, Bioethics, & Death

The teachings of karma in Hinduism and Buddhism are also reminiscent of the causal powers of conscious agents.

What of the Abrahamic religions? Nominally, Judaism, Islam and Christianity worship the same God, with a similar moral framework. But Judaism and Islam differ from Christianity in the Person of Jesus Christ, and it is Jesus Christ who serves as the critical link between physical and spiritual reality.

Judaism and Islam differ from Christianity in the Person of Jesus Christ, and it is He who serves as the critical link between physical and spiritual reality.

If we are to understand His importance, however, we must understand the context in which He appears. Bear with me as I recount a brief history of the Bible—I promise I’m leading up to something.

A Brief History of the Bible

The first five books of the Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy) were written by Moses at God’s command. The book of Genesis recounts creation, the flood and the formation of Israel through God’s covenant with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. The remaining four books are Moses’ firsthand experiences, including the plagues of Egypt and the exodus to the promised land, as well as the Law, received directly from God. Throughout the 40-year journey from Egypt to Canaan, God spoke directly to Moses, who wrote His commandments on tablets of stone. After the incident with the Golden Calf, when Moses breaks the tablets of stone in anger, God commands new tablets to be made, that the words could be rewritten and preserved (Ex. 34:1).

Israelites were commanded to follow the Law to the letter and teach it to the next generation.

The first commandments Moses recorded from Mount Sinai were the Ten Commandments, which related to worshipping God, keeping the Sabbath, and honoring parents and neighbors. In addition, He gave commandments regarding temple construction, feast days and sacrificial offerings. He also gave commandments regarding cleanliness, purification, diet, sexual purity, treatment of laborers, treatment of widows, orphans and foreigners, and so forth. The Law of Moses, as these passages are commonly called, was intensely practical, and Israelites were commanded to follow the Law to the letter and teach it to the next generation. God repeatedly warned the Israelites of the consequences of infidelity to His word.

After the death of Moses on the outskirts of Canaan, narration continues by the hand of Joshua, Moses’ assistant. The Book of Joshua recounts Israel’s conquests over the inhabitants of Canaan. It is a history, rather than a book of the Law. The Book of Judges then recounts the tumultuous period following the death of Joshua, as Israel settled in Canaan and was ruled by a series of judges—prophet-like figures whom God called from the various tribes of Israel to deliver His Word to the people. These figures were responsible for guiding Israel in conquest and ensuring that the Law of God was observed. At the end of the book of Judges, the tribes of Israel are divided across Canaan: “every man to his inheritance,” (Judges 21:24).

Israel continues without a unifying leader until the time of Samuel, who serves as a judge before anointing Saul, and later David, as king over Israel. This ushers in the era of the kings, recorded from the books of Samuel, Kings and Chronicles. But God still speaks primarily through the voice of the prophets, not the kings, during this time. It is important to note that the kingship was not ordained by God but was a request of the people that God chose to grant (1 Samuel 8:4-9). Thus, the role of king was purely political, and did not carry the spiritual weight of judge or prophet. It is not surprising, then, that the Israelites became increasingly unfaithful to God’s Law during this time, since they looked to the king for guidance, and the kings rarely heeded God’s prophets.

The role of king [in Israel] was purely political, and did not carry the spiritual weight of judge or prophet.

God’s warnings to Israel are recounted in the books of the prophets. This is also where the prophecies of the Messiah are recorded. The first explicit mention of the New Covenant appears in book of the prophet Jeremiah:

“…I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah [says the LORD].” - Jeremiah 31:31

The words of the prophets continue until the Babylonian captivity. The books of the minor prophets are interspersed throughout the times of captivity and Israel’s return from exile, concluding with the book of Malachi, who prophesies about the coming of John the Baptist and Jesus Christ:

“Behold, I send My messenger, and he will prepare the way before Me. And the Lord, whom you seek, will suddenly come to His temple, even the Messenger of the covenant, in whom you delight.” - Malachi 3:1

Prophecies of the Messiah also appear in the Psalms, the majority of which were written not by a prophet, but by a king. David was selected by God to reign over Israel after Saul, the first king, proved disobedient. David, more than any of the other kings, prayed directly to God and listened to the words of His prophets. He was the exception to the dichotomy of king and prophet, and it was through David’s line that God promised the Messiah would come. Thus, the coming of the Messiah and the New Covenant was established on both the spiritual level, in the words of the prophets, and the political level, in the words of the king in the Psalms of David.

Israel was therefore without excuse for failing to recognize Jesus as the Messiah when He fulfilled every prophecy and was of the house and lineage of David, and failing to acknowledge the New Covenant, in which we are united to God not by the Law but by faith in His Son.

The aim of both the Old and New Testament is to reclaim fallen man to God through the work of Christ.

The Symbolism of the Law

The aim of both the Old and New Testament is to reclaim fallen man to God through the work of Christ. The Old Covenant was intended to prepare Israel for the coming of the Messiah—the work He would do and why it was necessary. The concepts of the clean and the unclean and purification through the shedding of blood were vital to Christ’s ministry. Even in the most practical laws in the Old Testament, we see images of Christ. As Paul the Apostle explained: “The Law was our tutor to lead us to Christ.” And even God’s guidance in the conquest of Canaan and the rebuilding of the temple after Israel’s captivity was important for setting the stage for Christ’s coming. The physical time and place of Christ’s ministry, death and resurrection were not arbitrary.

In the New Testament gospels, Jesus took issue with the religious leaders for strictly enforcing the letter of the Law, while neglecting its “weightier matters—justice and mercy and truth.” “These you ought to have done, without leaving the others undone,” (Matt. 23:23). God was always concerned with the inner kingdom: the Law of Moses was a picture of it, the work of Christ was the real thing. This was something that the prophets understood, at least in part, but the religious leaders of Christ’s day did not. Thus, He says to them:

“You know neither the Scriptures nor the power of God.”

- Matt. 22:29.

After Christ’s death and resurrection, the Law—inner and outer—was fulfilled on our behalf, and the only requisite for reclamation to God was faith in Christ’s work and deity. But even with the fulfillment of the Law of Moses and the dissolution of the requirement for rituals and repeated offerings, a system of morality remains.

Most of the Jewish customs were relinquished by the church following Christ’s resurrection: things like feast days, Sabbath observance and diet (“He declared all foods clean”). These fell out of observance because they had outlived their spiritual utility. But things like sexual immorality, idolatry, theft, murder, and usury were still condemned, by Christ Himself and by His followers. These things relate to personal virtue, something that every lasting human civilization has formulated some concept of. Often, these concepts are similar, because there is an optimal set of virtues that tends to improve life for everyone. This is not unique to Christianity.

What the Scriptures put forth, especially the teachings of Christ, is that to every outward vice there is an inner, more fundamental component, which is the true sin. “If a man hates his brother in his heart, he has already committed murder.” The action is the only thing that matters to society, and thus abstinence from adverse actions is the only system of virtue that society can have. This is certainly something that can be optimized and, outwardly, looks a lot like morality. But to God, it is the inner sin that is important—the sin that society never sees.

To God, it is the inner sin that is important—the sin that society never sees.

The Apostle Paul refers to the Law of Moses as “a shadow and picture of things to come.” The symbolism of the Law is addressed at length in the New Testament, both in the teachings of Christ and in the letters to the churches. It wasn’t hidden from the Israelites in the Old Testament either: God was explicit about what the blood of the sacrificial offerings meant (“atonement for your sins”) and about the observance of feast days and fasts as memorials to God’s faithfulness to the Israelites. And through the words of the prophets and the Psalmists the symbolism of the Law was made abundantly clear.

But the role of the Law was not only symbolic. It was also practical. Laws of cleansing and diet kept the people healthy; laws for the justice system and for the role of the priests kept the society organized and unified. God was preparing Israel for its Messiah: both spiritually, through the symbolism of the law, and practically, through the utility of the law. The Law of Moses, and God’s insistence on memorials and the written word, were vital to Israel’s endurance as a nation until God’s work in them was complete. To this day, the Jewish people endure, despite centuries of persecution and near-annihilation, because of the traditions handed down from the Torah.

The Law of Moses, and God’s insistence on memorials and the written word, were vital to Israel’s endurance as a nation until God’s work in them was complete.

Morality and the Framework of Reality

Let us return to the question of morality, as it appeared in both the Old and New Testaments. A popular modern philosophy is that mankind developed systems of morality to optimize human existence: for a healthy society to exist, citizens had to abide by certain virtues. The secular view of morality is that certain things are “wrong” because they produce undesirable outcomes, either at the individual or community level or both. This has led to the reevaluation of traditional morals, particularly regarding sex, as society becomes better equipped to prevent undesirable outcomes like disease or the conception of an unwanted child. This is the logical conclusion of a physicalist interpretation of reality.

The secular view of morality is that certain things are “wrong” because they produce undesirable outcomes.

The Scriptures stand in stark contrast to this in two ways. First, in the Old Testament teaching that practical law is symbolic and that its physical benefits are not its primary intent. Second, in the New Testament teaching that sin is preexistent in the heart, and that a person is condemned before he/she commits an action that can have any consequences.

“For from within, out of the heart of men, proceed evil thoughts…”

– Mark 7:21

Man was created in the image of God because God breathed into him the Spirit of life. It is thus in the spirit that man relates to God, and it is this relationship that is played out in the things that are made. When we see the actions of man’s body play out in the world around him, it is only the ripples of some initial disturbance in his spirit. Society, with its power over the physical world, can manipulate the ripples, but the disturbance in the spirit persists. Thus, Jesus writes to the church of Laodicea:

“For you say, I am rich, I have prospered, and I need nothing, not realizing that you are wretched, pitiable, poor, blind, and naked.”

- Revelation 3:17

It is no contradiction that Jesus calls out the wealthy and prosperous, for whom the utility of the Law has produced the greatest benefit, as the most spiritually impoverished. To follow the law only, even if it brings you physical prosperity, is not sufficient.

When we see the actions of man’s body play out in the world around him, it is only the ripples of some initial disturbance in his spirit.

The Scriptures teach that man is restored to God by faith. Faith is not an action, but a state of being. Like any spiritual state of being, it produces ripples in the physical world: Jesus compares it to the wind, with only its effects being physically perceptible, and tells His disciples that their faith will be known by their works. But the effects are not the substance, and it is this distinction between effects and substance that is so difficult for secular man to comprehend. This is evident in the theories of reality discussed earlier, summarized in two major misconceptions:

1) Reality is fundamentally space-time and consciousness is a phenomenon thereof (physicalism).

2) Reality is fundamentally conscious agents that interact randomly to produce the illusion of space-time (conscious realism).

In rebuttal, I present the following:

1) Reality is fundamentally spirit (I use the religious term to avoid the confusion surrounding the term ‘consciousness’).

2) Space-time is neither arbitrary nor illusory, but a deliberate communication of spiritual reality.

The Witness of the Things That are Made

“But now ask the beasts, and they will teach you; and the birds of the air, and they will tell you; or speak to the earth, and it will teach you; and the fish of the sea will explain to you. Who among all these does not know that the hand of the LORD has done this, in whose hand is the life of every living thing, and the breath of all mankind?”

- Job 12:7-10

The Bible teaches that the physical universe is a witness of God. Everything that we perceive is created to teach us about Him, even our sin and the universal curse that resulted from it. Creation is the expression of God’s existence, just as human beings create art for no other reason than to assert their existence.

All of creation declares God’s existence, but it is the special role of mankind to understand it:

“For since the creation of the world His invisible attributes are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even His eternal power and Godhead, so that they are without excuse.”

- Romans 1:20

“It is good for me that I have been afflicted, that I may learn Your statutes.” - Psalm 119:72

If we think of the physical universe as the language of God, it suddenly becomes alive with meaning. It is only when we take it at face value, as random particles in motion, that it becomes a veil of confusion.

Throughout Christ’s ministry on earth, He performed miracles that flouted the laws of the physical universe in order to demonstrate His power over the things that are made. Mankind has always placed trust in the consistency of the world around him. Christ upset this consistency, and taught His followers to put trust in the fundamental power of the universe: Himself. The physical universe can teach us what God is like, but only by faith can we know who He is. Thus, to those He heals, Christ says:

“According to your faith let it be to you.”

– Matt. 9:29

And to those who ask for miracles, without any interest in Christ Himself, He says:

“A wicked and adulterous generation seeks after a sign, and no sign shall be given to it except the sign of the prophet Jonah.”

– Matt. 16:4

Christ never failed to provide signs—His miracles, His resurrection, and the witness of the universe from the beginning of time—but He asks for faith in Himself, not in the signs that point to Him. When His disciple Thomas declared he would not believe in Christ’s resurrection unless he put his fingers into the print of the nails, Christ says, after His resurrection:

“Reach your finger here, and look at My hands; and reach your hand here, and put it into My side. Do not be unbelieving, but believing.”

– Matt. 20:27

Thomas believed, of course, but Christ then says:

“Because you have seen Me, you have believed. Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.”

– Matt. 20:29

A complete framework of reality must consider the thing as it is, not as it is perceived, and this is a matter of faith. If we look no farther than the witness, we never find the real thing. The importance of Christ is that He became a witness—a human being who could be seen and heard—while retaining His deity.

The Gospel of John says of Christ: “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us.” He is called the Word because of the relationship He enabled between God and man: God speaks to us in a language that we can understand.

“My sheep hear My voice, and I know them, and they follow Me.”

– John 10:27

Why Does It Matter?

After all of this, what can be said of the belief that the framework or even the existence of reality is unknowable, because nothing can be proven?

It is true that nothing can be proven without first making some un-testable assumption about the universe. This is what it means to “live by faith, not by sight” (1 Cor. 5:7). To do anything in life, we need to believe in something, or at least espouse belief in it. To do science, we need to believe that the universe around us is real, with real consequences. We dismiss the belief that reality is unknowable and uncertain not because we can prove that it isn’t, but because it is not useful for us to assume that it is.

We dismiss the belief that reality is unknowable and uncertain not because we can prove that it isn’t, but because it is not useful for us to assume that it is.

I heard a friend state that she assumed she and the universe around her were real because it was useful for her to do so as a scientist, “but it doesn’t feel very certain.” This is exactly how it is supposed to feel. Christ taught that faith is the only certainty we can have in the physical realm, where everything is a shadow of reality. We await the day when faith becomes sight.

“Faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.”

– Hebrews 11:1

The Scripture teaches that the truth of the universe is slowly being revealed. We are given information in pieces, as we are able to comprehend it, until death lifts us from the realm of shadows and we comprehend in full.